FIRST «FIELD GUIDE» IN 1905

Prelude to the publication of the first “Field Guide” for bird identification

Chester A. Reed was a good teacher, but also a great communicator. It is not surprising that, in 1896, at his graduation from the Worcester Polytechnic Institute with a diploma in electrical engineering, he decided to join his father’s taxidermy enterprise.

Even though he was already recognized as an artist by his classmates at the polytechnic institute, his 2-years of training in technical drawing prepared him to communicate his long-time passion, the practice of ornithology.

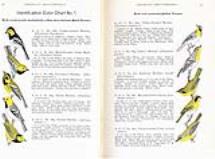

The magazine “American Ornithology for the Home and School, 1901-1906” (1) gave him the chance to show his talents as an artist, but also to introduce ornithology enthusiasts to bird observation. With that in mind, Chester published his first bird identification chart based on color characteristics in February 1902.

It was the first time that ornithology enthusiasts were provided with a technical tool that allowed them to identify birds easily from a distance, without having to kill the bird, a method that was commonly used at the time. The tool also showed many similar species on the same page, to ease their identification based on their respective characteristics.

The chart was revolutionary at that time. For the first time, bird drawings were made according to their technical identification characteristics and the colors were used to mirror the birds in the wild reliably. Chester’s academic artistic training helped him draw technical scale representations of each species.

Chester mastered the art of colors and drawing. In 1913, the magazine “AUK’ highlighted Chester’s characteristic talent. (2)

The chart was innovative in other technical elements that were important at the time of the publication of his first “Field Guide” in 1905.

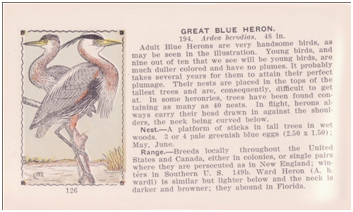

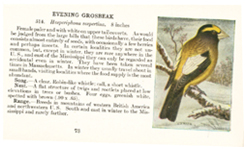

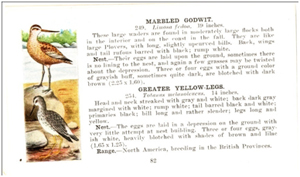

Every bird drawing was identified by its common name and its Latin name. A brief description of the bird, its environment, its nest, and its dispersion range allowed a quick identification of the bird. Putting together all of these facts in a few words showed Chester’s in-depth knowledge and expertise in ornithology.

For many of those reasons, Mr. Frank M. Chapman met with Chester and his father, Charles K. Reed (3), at their Worcester office, only a few days after the publication of the first identification chart in February 1902. Mr. Chapman picked up Chester’s original idea to produce a book that would take about two years to get published. The book “Color Key to North American Birds” was published in November 1903. It was the first book dedicated solely to the identification of different species of birds using their color characteristics.

For that reason, the birds were presented by color similarities instead of scientific groups. (3)

From that first book on bird identification, we had to wait 3 years before Chester A. Reed published his first “Field Guide” for bird identification in the field. (4)

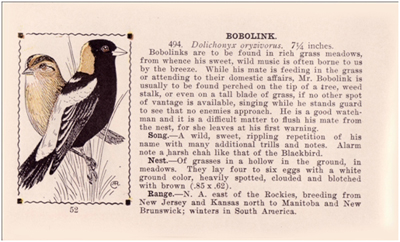

«“Bird Guide Part 2, Land Birds East of the Rockies” was published for the first time in November 1905. At that time, the “Field Guide” notion didn’t exist for ornithology enthusiasts. Chester chose a very simple title that showed what the book was about: “Bird Guide.”

However, the commercial phrase “Pocket Guide” made that first bird identification guide popular. At that time, ornithology books were mostly voluminous and were only useful as a reference for bird identification at home.

Chester’s “Pocket Guide” had many benefits. The first one was its dimension: it measured 3 inches by 5 inches and held almost 220 bird descriptions, which was revolutionary at the time. For the first time, ornithology enthusiasts were able to watch and identify a bird using a book in the field.

After its publication, this small book had a few more characteristics that made it among the most popular for nature study.

On one page, there was a technical drawing of the bird, its common and Latin names and its dimension. A few sentences described the bird and the female species if it differed from the male, with short notes on their behaviour.

A quick description of the bird’s song, its geographic dispersion and a description of its nest were other technical elements that could help identify it in the field.

At that time, when there were no identification books or binoculars to identify birds, the nest was an important element in the identification. Therefore, it was common to find a short description of the bird’s nest.

Another advantage that made the book user-friendly was that the bird was drawn on the outer side of every page. Then, it was relatively easy to find the bird that you were looking for, simply by leafing through the book.

After the publication of the first bird identification chart in February 1902, Chester A. Reed waited 3 years before publishing his first “Bird Guide” in 1905. (7) However, the second “Bird Guide” was released only a few months later.

In May 1906, the second bird identification book was published in the same format. It was 250 pages long and featured close to 230 bird species.

In that second identification book, Chester added more academic information to help bird enthusiasts familiarize themselves with the observed species’ different characteristics.

The success of the two books was probably responsible for the abrupt end to the publication of the magazine “American Ornithology” published by Chester since January 1901.

In the magazine’s editorial in August 1906, Chester mentioned that over 27,000 “Bird Guides” had been sold. It was then the last time the magazine “American Ornithology” was published. Since it was no longer being published, Chester had a writing opportunity that would influence the history of ornithology.

New printing technology allowed Chester A. Reed to publish books with state-of-the-art methods. A reprinting of the book “Bird Guide Part 2, Land Birds East of the Rockies” was printed with the 4-Color processing technique, in 1909, which improved the bird identification tool that had become essential.

The structure was the same, but the colors quickly became the main identification element, making life easier for bird enthusiasts. Chester then started using that technology for all of his publications. That’s how the “Bird Guide Part 1, Water Birds, Game Birds,” was published in 1910, using the same printing process.

That new printing technology opened doors for all of Chester’s publications.

Chester used two distinct books to show the whole group of birds east of the Rocky Mountains. In both cases, the general structure of the books was mainly based on the species’ popularity. The books didn’t follow the scientific presentation order.

It was not the case for the third book in the series “Bird Guide,” “Western Bird Guide, Birds of the Rockies and West to the Pacific.”

In 1908, Chester became curator for the Worcester Natural History Society. This position brought him in contact with scientists of that time. He kept his teaching vision by publishing books contributing to nature study in general. But in 1912, he published the book “Birds of Eastern North America” that, for the first time, used a more scientific approach in the presentation. The birds were presented using the Order, the Family, and the Species.

That job probably inspired Chester A. Reed for the publication of his third book in June 1913, “Western Bird Guide, Birds of the Rockies and West to the Pacific.”

Chester A. Reed passed away on December 16, 1912. In an article in the Worcester Sunday Telegram, on July 31, 1960 commemorating Chester’s life, his daughter, Mertice Reed Haynes, tells that her father had spent most of the fall of 1912, traveling across North America to study, draw, and take photographs of birds. That work was probably related to the preparation for his next “Bird Guide.”

He was not able to finish his work. However, over half of the drawings were made by Chester. It would be hard to speculate what portion of the text had been written by his father. The general presentation of the book followed Chester A. Reed’s style.

The book was the start of the “Field Guides” that we know today.

The format was the same as the other published books, thus making Chester successful with the “Bird Guides.” The order of presentation was then more scientific and showed the species using their Order and their Family.

There were other new elements to the book. The drawings showed more than one species which allowed one, in most cases, to compare birds with similar species of the same family.

By reducing descriptive texts and removing information about the bird’s song, Chester was able to provide descriptions of almost 550 bird species, including 230 drawing boards, showing close to 460 different species, all in a 250 page, 3×5 inch book.

If Chester A. Reed had not passed away so early, he might have adapted the first two “Bird Guides” to the new format.

Mrs. Anna Botsford Comstock (1854-1931) was an entomologist, an illustrator and a teacher very involved in nature study. She published a 900 page book, “Handbook of Nature Study,” in 1911, mainly aimed at teachers. It described a wide variety of nature-related topics to help educators teach about nature sciences. Her motto was “Nature through Books,” as opposed to the motto “Study nature, not books.”

In her book, Mrs. Comstock recommended many reference books, including Chester’s “Bird Guides” and “Flower Guide.” She recommended the use of Chester’s “Bird Guides” for 4th grade and older students.

The “Handbook of Nature Study” was very popular in the United States. The first edition was printed each year between 1911 and 1939. The following editions were published from 1939 to 1957, always with recommendations for Chester A. Reed’s books.

In 1916, the magazine “Bird-Lore,” an official publication of “The Audubon Society,” presented an article written by Mrs. Fay A. Ustick. The professor told about her experience of living with 4th Grade students learning ornithology. She explained the process that she implemented during the 1914-1915 school year. In that period, she created a junior Audubon club: “The Sharp-Eyes Junior Audubon Society of Columbus, Ohio.” The group was limited to 50 students. If a student missed 3 consecutive meetings, he was replaced by another student from the waiting list. (6)

In the article, Mrs. Ustick mentioned that most of her students owned Chester A. Reed’s book “Land Birds East of the Rockies” and were able to access reference books if needed.

There were 9,901 clubs of that kind in the United States, for a total of 205,138 members in June 1916. (7)

In 1917, the magazine “Bird-Lore” published the article “The Black-Capped Chickadee” in the “For and From Adult and Young Observers” section. The article gave in-the-field observations and described the bird’s lifestyle. In the reference lists, one can find Chester A. Reed’s “Bird Guide.”

The article’s author is G.T. Richards, 11 years old. (8)

Young people were not the only ones to be influenced by Chester A. Reed’s books. All ornithologists, enthusiasts and professionals, as well as naturalists who lived before the Great Depression, were influenced by Chester A. Reed’s “Bird Guides.” (9)

In 1919, at 11 years old, a young aspiring naturalist, member of his school’s “Junior Audubon Society” club, bought “LeMaire” brand opera binoculars and Chester A. Reed’s “Bird Guides.” Fifteen years later, he published a “Field Guide” that dramatically changed identification books of the time. His book “Field Guide to the Bird” would become the new standard in bird identification books during his life-time. The author is Roger T. Peterson.

Chester had many projects. In the preface of his book “Flower Guide, Flowers East of the Rockies” published in 1907, he mentioned that he had received many requests to use his idea of identification books and apply it to more nature-related topics.

He died too young to realize all of his projects and, most importantly, he never lived to enjoy the great success of his “Bird Guides.”

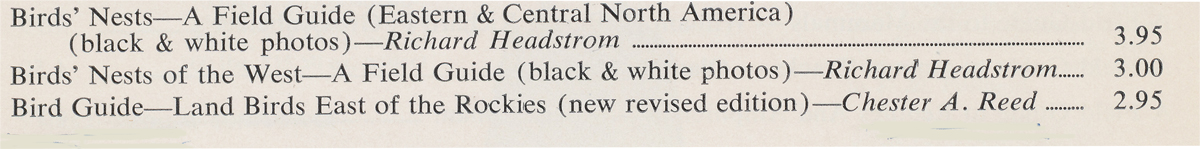

Between 1917 and 1941, over 919,000 books from the “Reed Guide” collection were sold :

That number does not include sales made between 1906 and 1916, or after 1941.

People agree on the fact that the “Bird Guides” were sold until the beginning of the 1960’s. However, the “National Audubon Society” offered Chester Albert Reed’s book “Bird Guide Part 2 Land Birds East of the Rockies” in their gift ideas section of their magazine in 1964. (14)

It would be reasonable to think that over 2,000,000 copies of the 4 identification books were sold between 1906 and the beginning of the 1960’s.

Nowadays, few people know Chester A. Reed. History seems to remember that he was the young artist who made the drawings for Mr. Frank M. Chapman’s book, “Color Key to North American Birds, 1903” and that his books were popular before 1934.

We seem to ignore that he influenced ornithology at the time when a new generation of people were becoming aware of the importance to know and protect their environment.

Of course, Chester was not the only one encouraging the respect of the environment or, to be precise, the protection of birds. In 1900, Mr. Frank M. Chapman initiated the first “Christmas Bird Count” to counter a tradition of the time that consisted of killing birds at a sports competition during the holidays. At the “Christmas Side Hunts,” people would kill birds, without thinking if they were of great beauty, beneficial to the environment or rare. The winner was the person who had killed the most birds.

A wide majority of the people who intervened at the time were scientists. Chester became well-known for his abilities at popularizing and introducing people of all ages to bird observation by providing them with tools that changed the ornithology hobby.

In 1912, when he published two small books, “Illustrated Bird Dictionary and Note Book, Land Birds” and “Illustrated Bird Dictionary and Note Book, Water and Game Birds,” he put together a tool kit that would help the practice of the hobby. (15)

Since that time, all pieces useful to bird observation were available: color identification books for in-the-field observation, two small notebooks to write down observations, as well as many ornithology books to complete general knowledge of the subject. He also published a book on the photography of birds in 1911: “Camera Studies of Wild Birds in their Homes.” That way, he covered all the tools needed to practice ornithology, for young beginners to experienced enthusiasts.

For that reason, in December 1932, the “Worcester Natural History Society” and Worcester’s “Forbush Bird Club” came together to create the “Reed Ornithological Library” to commemorate Charles K. Reed and Chester A. Reed’s participation with the issues of the Society and their great contribution to science and to ornithology in American ornithology history.

For many people, there was no “Field Guide” before the publication of the first “Field Guide” by Mr. Roger T. Peterson in 1934. However, at the beginning of the 20th century, ornithology became popular, and Chester A. Reed’s publications played an important role in the growth of the activity.

Nowadays, the “Field Guides” have evolved a lot. Just like any other entity, there is always a first time. Chester A. Reed’s three “Bird Guides” lead the way for the evolution of today’s bird identification books.

If people were to be considered a pioneer of ornithology, Chester A. Reed would hold an important spot amongst these people who were innovative for our inspiration. We should give him the recognition that he deserves.

You can consult the slideshow of the presentation.