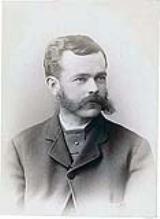

Charles K. Reed, Businessman “Artist”

Charles Keller Reed

1851 – 1921

Charles Keller Reed, taxidermist, ornithologist, naturalist, artist, and writer and editor of books on nature, illustrated with natural colors by his son, Chester A. Reed. (1)

Charles Keller Reed was born on April 20, 1851, in Huntington, Hampshire, Massachusetts. In 1855, when he was four years old, his father, Samuel Worcester Reed, moved to the South of Boston. Charles then received his education from the Boston public schools. In 1865, his father moved again, to Providence, Rhode Island, for work. Even at that time, Charles showed an interest in nature and everything concerning it. (18)

On July 6, 1873, Charles K. Reed married Carrie Bosworth in Barrington, Essex, MA. Two years later, in 1875, he started a pet shop business in the Lincoln Block at 368 1-2 Main Street, in Worcester, Massachusetts.(2)

Probably around 1882, Charles became associates with Mr. H. L. Rand, a taxidermy artist, who shared Charles’ passion for the art of taxidermy.

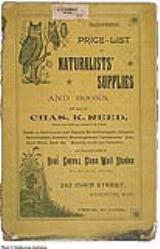

A few years later, Charles moved the store to 262 Main Street. In 1887, he bought the enterprise “The Naturalists Exchange” from Mr. Edward W. Forbush. (3) He promoted his boutique and his products actively.

Here are two catalogues produced in 1890 for a specialized clientele:

For naturalists (1890) (P3) |

For oologists (1890) (P4) |

He also published ads in specialized magazines regularly.

“The Mineral Collector”, May 1895 (P5) |

The Museum», January 1895. |

In 1897, a fire destroyed his boutique (2)(2) forcing him to move to 75 Thomas Street. Here is the first ad for his new boutique in the magazine “The Museum,” in August 1897. (P7)

His new boutique offered naturalized specimens and all the products required for taxidermy, entomology, oology, as well as a large collection of shells, minerals, butterflies and eggs.

Charles proudly poses in front of his new boutique at 75 Thomas Street, in Worcester. (P8)

In 1908, he moved again, to 238 Main Street in Worcester. The Audubon movement for the protection of birds was getting bigger, and new legal restrictions on the collection of birds or eggs were slowly surfacing so Charles gradually stopped practicing taxidermy, to focus on activities of the ornithology hobby in general. He stayed at the same address until he retired. We can see Charles at the window of the boutique. (16)

(P16)

«Nature Books»

Please notice the arms on the picture of the boutique, clearly shows Charles’ new vocation for Nature Study.

Between 1901 and 1915, Charles edited 35 books on the hobby of nature, as well as postcards, photography, and small colored picture cards illustrated by his son Chester, usually with his printing partner, Mr. A. M. Eddy d’Albion.

All books edited by Charles were Chester’s publications, except for one: “Guide to the Mushrooms,” by Emma Taylor Cole, 1909.

Charles wrote three books. His first book was “Guide to Taxidermy,” in 1903. He published a revised version in 1908 with his son Chester. His third book, “Animal Guide,” was published in May 1915. (14)

ici

His biggest success, without a doubt, was the publication of “Bird Guides” on bird identification, published by his son Chester.(15) The series contributed to the development of a new concept and was the start of many other books on the joys of nature observation. He created a collection: “Nature Guides.” (P19)

The “Field Guide” collection included: (P20):

• Land Bird, Bird Guide , 1905

• Water Birds, Bird Guide, 1906

• Flower Guide, 1907

• Western Bird Guide, 1913

• Tree Guide, 1914 (by Julia Ellen Rogers )

• Animal Guide, 1915

Please note: What’s extraordinary is that Charles’ and Chester’s books were sold until the beginning of the 1960’s and, even today, it is possible to buy many of their books, re-printed by editors specializing in rare books. Some websites are specialized in the sale of that kind of book.

While he was at it, Charles commercialized a pair of binoculars branded “Reed Nature Study Glasses,” between 1913 and 1914. Charles’ innovative spirit showed until the end. (P21)

An Innovative Artist…

|

||

At the Jamestown Exposition in 1907, Charles received a GOLD medal in the “Ornamental Taxidermy – Game Birds under Convex Glass” category. His talents as an artistic taxidermist were officially recognized. (P12) |

||

Charles produced the catalogue “Game Birds,” in which he offered 112 styles of framed birds in different sizes. Please consult the “Photo Gallery” section to see the catalogue. (P9) |

||

Here is item #61 offeredin Charles’s catalogue |

And here is an original of the same model preserved by the Reed family |

|

| This original was made by Charles’ son, Chester A. Reed. We can notice the frame made out of white birch bark, indeed in Chester’s style.

Here are some more of Charles’ realizations that show his artistic talents. |

||

Butterflies board (P13) |

Butterflies board (P14) |

Butterflies board (P15) |

He also painted. Here is a painting that he made in 1918. Please notice the frame made out of seashells. Charles always liked seashells. There is a similar painting in the Reed family’s private collection. (P22) |

||

He excelled in black and white art. He produced his ads himself for the magazine “The Oologist.” The Oologist, Vol. XI, No. 1, January 1894  The Oologist, Vol. XII, No. 4, April 1895 |

||

He also produced this picture for the first issue of the magazine “American Ornithology for the Home and School” in January 1901. He produced many more ads in the magazine. |

||

Charles Keller Reed was a great artist

Traveller for Leisure, Nature Study and the Adventure

Charles travelled a lot in his life-time.

In 1886, he participated in a 3-month trip to Florida with Mr. Edward W. Forbush, Mr. H. L. Rand, Mr. John Farley, Mr. Frank Morse and two others to hunt and collect specimens. In 1897, he visited California and British Columbia to study nature. In 1899, he went on a caribou hunting trip to Labrador. (4)

Trip to the Arctic Pole

The trip that made the news was the one he went on with Dr. Frédérik Cook in 1894. He left New York on June 27. They had planned to travel for 3 months, but the ship, “The Miranda,” hit an iceberg by the coast of Labrador and was too damaged to continue the trip. Here is a sketch from Charles’ personal expedition journal, showing the meeting of “The Miranda” and the iceberg, on July 17, 1894. (P26)

The ship had to return to the St-Jean harbour in Terre-Neuve for repairs. The accident could have been dramatic. A few days later after visiting the area, he went back to Worcester without having reached the goal of the expedition: to visit the Arctic Pole. (19) In this picture, Charles is the third from the right, in the back row. He is under the blue line drawn by Carrie B. Reed. (P26)

Expedition map (P27) |

Page 1 |

Page 2 |

||||||

| List of the expedition members in 1894 (P28)

Charles is the third one from the bottom of page 2. |

||||||||

A Great NaturalistIn 1890, Charles K. Reed became a member of the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) (5), but only for a short period. At an AOU meeting in 1887, Mr. F. S. Webster manifested his discontent against people considered as enemies of the association. He recognized that taxidermy was used in science, but he disapproved the practice of collecting them for pleasure, without scientific justification. The debate only intensified with time.(6)

|

||||||||

For that matter, in 1904, the New York Audubon Society accused Charles of naturalizing birds and eggs against new laws in force for the protection of birds.(8) A year later, on April 1, 1905, Charles announced that he had sold his entire egg collection to Dr. Frank H. Lattin in the magazine “The Oologist,” vol. 23, no. 5, page 67.

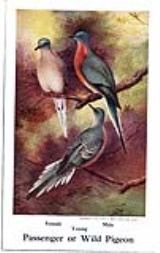

However, in 1910, Charles showed great interest for the protection and conservation of birds by contributing to a research program implemented by the American Ornithologists’ Union in America. It aimed to trace back the last specimens of endangered species in the wild, the passenger pigeon.

In 1910, Charles published a 4-page leaflet, illustrated by his son Chester, to help identify the passenger pigeon and find a living specimen in the wild. Charles and Chester invested $400 in the leaflet, which was widely distributed in the United States.(10) You can see the leaflet in the “Photo Gallery” section.

On June 30, 1914, Charles became a member of the Worcester Natural History Society.(4) The whole family (Charles, Carrie and Chester) were involved in the society.

Charles frequently published ads in different magazines of the time. He discovered, with time, the benefits and the selling power that a specialized magazine in a scientific leisure would represent. He advertised regularly in the “WANTS, EXCHANGES, AND FOR SALES” section of the magazine “The Museum” to exchange or sell his products. He quickly built his reputation among the magazines readers.

Mr. Walter F. Webb, editor of the magazine “The Museum,” then introduced Charles K. Reed to his readers on May 15, 1896.

«Just before going to press we were pleased to welcome at our office Mr. Chas. K. Reed of Worcester, Mass. Doubtless most of our readers have heard of him, as he is a believer in printer’s ink and has persistently used the columns of the Museum and with unusual success. His specialty is taxidermy work in all its varied branches, although he at all times carries a very large stock of eggs, skins, shells, curios, minerals and naturalists supplies.» (12) (P36)

Starting in 1898, the magazine “The Museum” had financing troubles. It was not supported by the large community of ornithology writers. In March 1900, the magazine ceased to exist. It was combined with another magazine edited by H. W. Keer. (13)

Charles chose that moment to plan his own magazine dedicated exclusively to the study and protection of birds. He took advantage of an ideological trend getting more favourable to bird study and observation to get the support of ornithology writers of the time.

Charles had the experience and a natural business sense to jump into the new adventure. His son, Chester, had in-depth knowledge of ornithology, was an expert illustrator envied by his peers, had a natural talent as an educator, and was always willing to share his knowledge.

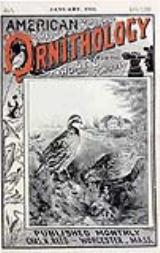

The “American Ornithology for the Home and School” magazine was born and was published for the first time on January 1st, 1901. (23) (P25)

The magazine “American Ornithology for the Home and School” was structured mostly like the magazine “The Museum.” It had various articles, a section for the sale and exchange between readers, and the sale of advertising spaces. To ensure a quick and efficient production, Charles had the magazine printed by Mr. A. M. Eddy d’Albion in New York, the same one who printed the late magazine “The Museum.” Mr. Eddy became Charles’ business partner for his future publications.

The magazine was published until August 1906. Over 1,500 pages (24) and 67 magazines were read monthly by readers in the United States, Canada and Mexico. According to a personal evaluation (website author), I estimate that the magazine had between 60,000 and 80,000 subscribers in August 1906.

Here starts the Reed family’s influence in the ornithology hobby history in America, at the beginning of the 20th century.

The time to retire arrived. In 1916, Charles started selling his assets. He then sold the copyrights for the books that he had edited to his business partner, “Doubleday, Page & Company,” in exchange for royalties that he would receive until the end of the publication rights. After his death, the royalties were given to his wife, Carrie Bosworth Reed, then to their daughter, Mona Reed King, and finally to their granddaughter, Doris Reed King Gibbins.

His whole collection of postcards, birds, flowers, and small colored pictures were sold to Mr. G. P. Brown de Beverly, in Massachusetts, in 1916.

On January 1, 1917, he finally took the big leap. He sold his store “Reed’s Bird Store,” located at 238 Main Street, Worcester, to Mr. Clifford Sorenson. (16)

From then on, he enjoyed his free time to read, paint and travel.

In 1919, at 68 years old, Charles made a request to get a passport. The document tells us that he measured 5 feet 7 inches, and that he had a square chin, brown eyes and grey hair.

His passport was issued in November 1919. Charles and Carrie then went on a 6-month trip to Cuba and Jamaica. They left New York on December 9, 1919, on the “United Trust Line.”

(32)

His reputation preceded him in Jamaica. When Charles visited the Institute of Jamaica on December 17, 1919, he was elected as a member of the institution in recognition for his contribution to Natural History.

(33)

During their trip, they took many pictures that Carrie kept in a small journal describing their adventures and their discovery of the country with enthralling sceneries. When reading the journal, one can see that they still had a passion for nature and birds. Carrie regularly wrote about the observation of birds that they had met on the trip. (22) Here, we see Charles and Carrie at a photo shoot on February 22, 1920, in Kingston, Jamaica. It was probably one of their last official pictures taken together.

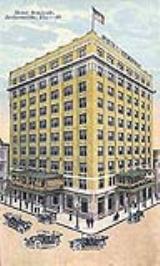

Charles passed away suddenly on March 11, 1921, at 70 years old. He felt faint on a train between St. Petersburg and Jacksonville, Florida. He died at Seminole Hotel in Jacksonville. This picture shows the Seminole Hotel in 1920. (2)

Many people in Worcester recognized his great contribution to the study of plants and birds. He was also known as the best taxidermist in town. He still owned a collection of shells and plants.

A few years later, the Worcester Natural History Society created a book collection named the “Reed Ornithological Library” to highlight the importance of his contribution to ornithology. (21) (34)

The funeral was held at his home, at 11 State Street, in Worcester. He was buried at the Forest Hills Cemetery in Barrington, Rhode Island. (P35)

Charles Keller Reed 1851 – 1921

Here is the slide show of the presentation.

(1) Presentation given by Carrie Bosworth Reed in a genealogical summary on Charles. I personally added the title of taxidermist (author of the website).

(2) Gazette Worcester, March 14, 1921

(3) May, John H. 1928. Edward Howe Forbush: A biographical sketch. Proceedings of the Boston Society of natural History, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 33-63, 2 pl.

(4) Biographical note on Charles documented by Carrie Bosworth Reed. March 30, 1910, Reed family archives.

(5) “The AUK” Volume VIII, page xx, “Officer and Standing Committees of the American Ornithologists’ Union, 1890-1891”

(6) “The AUK” Notes and News, January 1887, Volume 4, Number 1, page 82.

(7) “The Museum” March 15, 1896, page 145

(8) A brief History of American Birding, Scott Weidensaul, page 198

(9) The Oologist magazine, Volume 23, 1906, page 67.

(10) “The AUK,” Volume 18, January 1911, “The Passenger Pigeon Investigation” by C. F. Hodge, pp. 52.

(11) “The Museum” Volume 1, Number 1 remove this quote

(12) “The Museum” Vol. II, No. 7, May 15, 1896, pp. 185.

(13) A Bibliography of Scarce or Out of Print, North American Amateur and Trade Periodicals Devoted More or Less to Ornithology by Frank L. Burns, 1915

(14) For more information, consult the “Charles Editions List” section.

(15) For more information, consult the “Pockets Guides” section.

(16) Biographical note documented by Carrie Bosworth Reed.

(17) Consult the “Charles K. Reed’s Advertising Illustrations” section.

(18) wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com, ID : I73330, Carrie B. Reed’s biographical note.

(19): Worcester Sunday Telegram, August 1894

(20): Reed family archives

(21): For more information, consult the “Carrie B. Reed” section.

(22): Reed family archives

(23): For more information, consult the “American Ornithology for the Home and School” section.

(24): “Copyright Book” list documented by Carrie B. Reed

P1 : Charles in 1888, Reed family archives

P2 : Reed family archives

P3 : Smithsonian Museum’s archives

P4 : Smithsonian Museum’s archives

P5 : “The Mineral Collector”, May 1895

P6 : “The Museum”, January 1895, Page 92

P7 : “The Museum” August 1897

P8 : Reed family archives

P9 : Reed family archives

P10: Reed family archives

P11: Reed family archives

P12: Reed family archives

P13: Arrangement of plants and butterflies, Reed family archives

P14: Arrangement of plants and butterflies, Reed family archives

P15: Service platter with a layout of plants and butterflies, Reed family archives

P16: Charles’ store at 238 Main Street, Worcester

P17: Arms on the front of Charles’ store at 238 Main Street, Worcester

P18: Advertising card on Charles’ books

P19: Small catalogue with a list of Chester’s and Charles’ publications

P20: Reed family archives

P21: Reed family archives

P22: Reed family archives

P23: The Oologist, Vol. XI, No. 1, January 1894

P24: The Oologist, Vol. XII, No. 4, April 1895

P25: American Ornithology for the Home and School, January 1901

P26: The Last Cruise of the Miranda, by Henry Collins Walsh, The Transatlantic Publishing Company, 1895. (Reed family archives)

P27: Reed family archives

P28: Reed family archives

P29: Reed family archives

P30: The Museum, Vol. II, No. 5, March 1896

P31: Reed family archives

P32: Reed family archives

P33: Reed family archives

P34: Seminole Hotel in Jacksonville, Picture from a postcard in 1920 Familyoldphotos.com

P35: Archives de la famille Reed.

P36: Reed family archives

P37: The Museum Vol. II, No. 7, May 15, 1896, page 185